ISSN: 1130-3743 - e-ISSN: 2386-5660

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.27805

THE RUPTURE OF EDUCATION: PERSPECTIVES FROM PEDAGOGY AND SOCIAL EDUCATION

La educación escindida: perspectivas desde la pedagogía y la educación social

Xavier ÚCAR

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. España.

xavier.ucar@uab.cat

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3678-8277

Reception date: 26/11/2021

Acceptance date: 04/02/2022

Online publication date: 01/09/2022

How to cite this article: Úcar, X. (2023). The Rupture of Education: Perspectives From Pedagogy and Social Education. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 35(1), 81-100. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.27805

ABSTRACT

Is social education a specific and differentiated type of education? What differentiates it from other types of education? Is there any education or pedagogy that is not social? How are pedagogy and social education related to these other, also specific, types of education? These are some of the questions that guide the conceptual and historical journey undertaken in this work from the perspective of pedagogy and social education, based around what we have characterized as ruptures in education. The underlying idea is that various ruptures have occurred in the field of education over the past century within the framework of the predominant analytical perspective. Four specific ruptures are identified and analysed: (a) that which classifies the universe of educational actions in three areas: formal, non-formal and informal; (b) the difference between pedagogy and educational sciences; (c) that which identifies three differentiated types of pedagogy: family, school and social; and (d) that which divides the field of Education at university into so-called areas of scientific knowledge. The work closes with an interpretation of the connections that currently structure these ruptures in education.

Keywords: Pedagogy; educational sciences; social education; social pedagogy; formal education; non-formal education; informal education; undergraduate university training.

RESUMEN

¿Es la educación social un tipo específico y diferenciado de educación? ¿Qué es lo que la diferencia de otros tipos de educación? ¿Hay alguna educación o pedagogía que no sea social? ¿Cómo se relacionan la pedagogía y educación social con esos otros tipos, también específicos, de educación? Estas son algunas de las preguntas que, desde la perspectiva de la pedagogía y la educación social, orientan el recorrido conceptual e histórico que se desarrolla en este trabajo alrededor de lo que hemos caracterizado como escisiones educativas. Se parte de la idea que, al amparo de la perspectiva analítica predominante, se han producido a lo largo del pasado siglo, diversas escisiones en el campo de la educación. Se identifican y analizan cuatro escisiones concretas: (a) la que estructura el universo de las acciones educativas en tres áreas: formal, no formal e informal; (b) la que diferencia entre pedagogía y ciencias de la educación; (c) la que clasifica tres tipos diferenciados de pedagogía: la familiar, la escolar y la social; y (d) la que estructura el sector universitario de la educación en las denominadas áreas de conocimiento científico. Se cierra el trabajo con una lectura de las articulaciones que estructuran en la actualidad aquellas escisiones educativas.

Palabras clave: Pedagogía; ciencias de la educación; educación social; pedagogía social; educación formal, educación no formal; educación informal; formación universitaria de grado.

“After passing through the analytical tunnel, freer synthetic forms are possible again, forms of life endowed with a supplement of poetry and more freedom of movement” (Sloterdijk, 2016, p. 95).

Is social education a specific and differentiated type of education? If so, which of its features make it specific? What makes it different from other types of education? Is there any education or pedagogy that is not social? How are pedagogy and social education related to these other, also specific, types of education? These are some of the basic questions that guide the conceptual and historical journey that will be undertaken in this article based on what we have characterized as educational splits.

To achieve the above goal, I take as a starting point the idea that education and pedagogy have been ruptured or, in other words, that there are many educations and pedagogies that supposedly have a specific entity in themselves and differ from one another on the basis of a very diverse set of criteria. A rupture is more than a mere division or fragmentation from an initial unit; it is an exclusive differentiation that can end up asserting its own identity over time, one which is specific, constitutive and differentiated from both the original unit and all of the other objects that have split away.

It is probably in the early modern period when this general tendency towards dividing phenomena first emerged. And it did so in the guise of the analytical perspective, which at the time seemed to be the most up-to-date, fastest and best means of discovering and mastering the mysteries of life (Sloterdijk, 2016). Dividing phenomena in order to specify, clarify, differentiate and understand them. Always under the premise, which may seem somewhat I today, that analysis leads to mastery and that only through the latter is it possible to achieve a deep and true knowledge of things.

From this perspective, everything is removable, deconstructible and fragmentable. Throughout the last two centuries, many dimensions and phenomena of human existence have operated through rupture. Everything is deconstructed for the sake of greater and better knowledge, which does not in fact seek anything other than a greater control over reality. Although the disciplines seemed to be the last redoubt in the academic field, under the banner of a prevailing specialization, they also ruptured into areas of knowledge and areas of research, action and intervention that enjoyed greater or lesser autonomy.

The field of education and pedagogy has been no exception and, in its journey from the simple to the complex, has experienced numerous ruptures, many of which are still in force today. Gone is the “school of life” and the “total knowledge” that Comenius to referred in the 17th century1.

A current look at education reveals not only a very complex panorama, but also numerous ambiguities, overlaps and conceptual and methodological inaccuracies that do not seem to have been fully resolved. It is not only the fact that anyone can talk about education, apparently fully informed for the sole reason of being a parent. It has often been the educational profession itself and also the media who, preferring to amplify certain discourses, have largely contributed to the confusion about the what, who, how and where of education in our current societies. This was first discussed by Trilla (2018) in a work on what he called “the reactionary trend in education”. It refers to:

exposing the spectacular frivolity of certain great men of culture when they comment on education. Refuting the, truly arbitrary, phobias of some teaching professionals who attribute all evils to any educational innovation that might arise. Referring, explicitly and by name, to two groups with opposing ideologies, but both with clearly sectarian behaviours. And also confronting the two types of “lefties”: those who dedicate their time to reinventing garlic soup; and those who also claim to do so scientifically (p. 190).

The trend the author is referring to has undoubtedly contributed to generating a lot of spurious noise, and also to hindering a well-founded and serious debate in society regarding the current realities and problems surrounding education. Beyond this, however, we must point to a whole series of ruptures that were developed or incorporated into the theoretical and practical educational heritage throughout the 20th century, and probably in line with what was happening in the other social sciences in Spain. The school and the community, the academic and the social, reason and emotion, theory and practice, content and activities, the qualitative and the quantitative, academia and the professional arena, these are but a few examples of the ruptures to which we refer.

Such ruptures are becoming more evident today, given the path towards the visibility and understanding of complexity that began in the final quarter of the last century. It is a path that emerged as a result of the ideas and concepts available at the time proving themselves to be manifestly incapable of an in-depth and adjusted approach to the complexity of phenomena. In the face of such incapacity, conceptual and methodological hybridizations and permeabilizations were devised that proposed a rethinking of the borders that had been erected between phenomena, and in some way reconnecting and reinterpreting what had previously been ruptured. Concrete examples of this path include mixed research methods, which aim to overcome the rupture between qualitative and quantitative methods; the so-called bio-sciences, which seek to amalgamate biology with the rest of the natural sciences; and finally, and among many others, the perspective of “learning to learn”, which aims to transcend differentiation between content and procedures. Since that point in time, we have continued to strive in this general search for articulations that provide more precise, integrated and complete perspectives of a socio-educational reality that we know to be complex.

Regrettably, it should be noted that Spanish authors of the last century generally made few significant and original contributions in the field of education. Furthermore, education in this country was mainly developed through the importing of theoretical models and conceptualizations from other countries. These were therefore models and conceptualizations developed in other traditions that, combined with and/or adapted to our own reality, rarely fit well within a more or less ordered and coherent framework. Perhaps because it is poorly structured, holds a less than clear status somewhere between practice, science and art, or ultimately functions on the periphery of or directly outside the education system, the field of pedagogy and social education has been especially sensitive to these ruptures.

I will exemplify the above idea be presenting four phenomena, each the result of ruptures in education, which have had a broad impact on shaping the education and pedagogy field in this country. They are ruptures that have clearly affected the development and evolution of both education and social pedagogy. What social education represents today in Spain, both in terms of an initial university education and as a profession in itself, is a direct result, among others, of the ruptures in education that I propose here.

I am not so much interested in delving into each of these ruptures, as showing how they have influenced or determined the evolution of pedagogy and social education in this country. The ruptures I am referring to are as follows:

1. That which classifies the universe of educational actions in three areas: formal, non-formal and informal.

2. That which differentiates between pedagogy and the educational sciences.

3. That which identifies three differentiated types of pedagogy: family, school and social.

4. That which structures the field of Education at university into so-called areas of scientific knowledge.

1. HOW THE UNIVERSE OF EDUCATIONAL ACTIONS IS STRUCTURED

This rupture in the universe of education became popular in the 1970s when Edgar Faure published his well-known text Learning to be as part of a UNESCO initiative. Since then, all educational actions have been classified as falling within one of three areas: formal, non-formal or informal.

The way in which the areas were characterized left no room for doubt about how the three types of actions are to be considered within the educational panorama, and especially in relation to schooling and the education system. Formal referred exclusively to the latter two. Non-formal was proposed as an extraordinarily diverse bank of educational experiences that accommodated anything not considered formal; that is, that did not fall within the education system. Ortega ironically pointed out that it was in the formal sphere where “true pedagogy and education” were to be found (2005, p. 21), this being clearly attested to by the undervaluing throughout much of the 20th century of socio-educational activities included within social education today.

Social education itself is a good example of the fragility inherent in the rupture of formal and informal. In 1991, university studies in social education were made official in the Spanish Official State Gazette (B. O. E.) and therefore became part of the formal education system. Until then, the training of what are now called social educators (then called specialized educators; sociocultural animators; adult literacy instructors; leisure time education monitors; occupational trainers; and a long etcetera) was offered by municipal bodies and included within so-called non-formal education.

Despite the importance still awarded to non-formal education in some Latin American countries today, where it is seen as an educational sector with an entity in itself, in Europe it has ended up as a simple administrative delimitation based around obtaining valid academic certificates. Training that offers such certificates is considered formal, and the rest non-formal.

Although the informal sphere was recognized as existing back then, due to its characteristics as an intangible environment that was unlikely to be formalized, or so it was thought, its influence was either not taken into account or was minimized. The perspective of complexity provides a different view. Informal learning is currently considered an emerging and promising area in the field of education, and especially in social education, which focuses its work on people’s everyday lives. An area that, still today, is underexplored and requiring of further research.

How is social education related to these ruptures in education, and more to the point, with which of them is it most related? It is no easy question to answer given its development in Spain. Until not long ago, the immediate answer might have been that social education falls within the sphere of non-formal education. In historical terms, it is true that, as an alternative to school, social pedagogy had been developed outside the formal arena, in dealing precisely with all those individuals who could not access or had been expelled from school for whatever reason. Perhaps this is why Fermoso (1994, 2003) stated that social pedagogy deals specifically with non-formal education.

The B.O.E. of October 10, 1991 (Royal Decree 24669-1420/1991), which contained the first guidelines on studies related to the Diploma in Social Education, stated that:

Teaching should be oriented towards training educators in the fields of non-formal education, adult education (including the elderly), the social integration of maladjusted and disabled people, and socio-educational action (p. 32891).

I have published an in-depth analysis of the inconsistencies in this wording from both a technical and epistemological point of view elsewhere (Úcar, 1996). Suffice it to say here that it is evident, in the definition itself, that the non-formal sphere falls short when it comes to specifying those spaces and times in which social education acts. From the perspective of lifelong learning, Caride (2020) provided a detailed anlaysis of the theoretical-conceptual inconsistencies of non-formal education, highlighting international organizations’ use and abuse of the term. Said author also revealed the insufficiencies of this expression in encapsulating the complexities of other educations, including among them social education itself.

In recent years, social education has begun to transcend the limits that had historically confined it to working exclusively with people in situations of need, deficit, risk and vulnerability. The classic idea that all education is social by nature is beginning to become a reality in our country. It should be noted, however, that if any one type has truly represented social education, then it has been that of school education, since it brings children together to socialize them and enable them to live together in society. However, since the earliest of times, it was those educational actions taking place outside the school framework that were characterized as “social”. Probably due to the negative connotations that accompanied this concept in the early modern period

The incorporation of social educators in schools was first institutionalized in Spain in 2002 (Galán Carretero, 2019), and five Autonomous Regions now contemplate this in their respective legislation: Castilla-La Mancha (2002), Extremadura (2002), Andalusia (2008), the Canary Islands (2018) and the Balearic Islands (2018). Others, such as Catalonia, are currently implementing pilot projects to do likewise. In fact, there has been widespread analysis and debate on social educators’ connections and contributions to schools in recent years throughout Spain2. This debate coincides with a parallel movement committed to connecting the school with the community (Castro et al., 2007). There is already talk of “school social pedagogy” (March and Orte, 2014, p. 75), and it seems highly likely that incorporation of the profession of social education within the education system as a whole will become the norm in our country in the coming years.

Despite the initial usefulness of dividing the universe of educational actions into the three aforementioned spheres, it has always been difficult to fit pedagogy and social education within this framework. The simplicity of the approach means it is inappropriate for precisely characterizing spaces and times in education today. It is worth remembering that half a century has passed since it was first formulated, and given the accelerated change that our societies have experienced in recent decades (Rosa, 2012), it is therefore not surprising that it has become practically obsolete today.

2. PEDAGOGY AND/OR EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES

This differentiation is not, at its origin, the result of a rupture within the educational field, but rather due to two European scientific traditions that arrived in Spain during the 20th century. The first, German, was idealistic in nature, and the second, the Franco-British tradition, was positivist (Ortega, & Caride, 2015, p. 7). In other words, one tradition more focused on philosophical aspects, and another more focused on the scientific, the empirical and the practical3. If I refer to this as a rupture, it is due to the way in which the two traditions were treated in this country, the relationships that were established between them and a certain conceptual confusion derived from said relationships. Both had a notable influence on the creation of two university qualifications at the beginning of the 1990s: the Bachelor’s degree (in Spanish, licenciatura, a 4-year course) in Pedagogy, and the Diploma in Social education (3 years). Expanding on this rupture can help us understand some conceptual and professional problems that occur between what, in the Spanish context, comprise two different 4-year university degrees today: those of Pedagogy and Social education. A rupture that could lead us to think that these are two completely different university degrees.

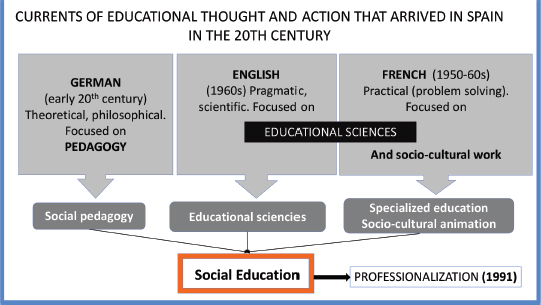

As a discipline that connects with a philosophical tradition, pedagogy stems from the Germanic influence and it was in this line that the first allusions to social pedagogy appeared from the beginning of the 20th century onwards (Ortega, & Caride, 2015). For its part, the Franco-British tradition came to our country at the beginning of the second half of that century. Despite being from two different sources, France and England, and the different approaches they entail, both coincide in proposing a pragmatic perspective, closer to social reality and educational practice than the German. And they also coincide in not referring to pedagogy, but rather to education exclusively. It was this latter tradition, especially the more practical and applied dimension of the Francophone line, that led to the social education we know today. An overview of this analysis can be found in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

EUROPEAN EDUCATIONAL TRADITIONS THAT CONVERGED IN THE PROFESSIONALIZATION OF SOCIAL EDUCATION IN SPAIN

Source: author’s own work

In the last quarter of the 20th century, pedagogy and educational sciences coexisted in education studies in our country, without it being very clear what the differences were between them or whether the former included the latter or vice versa. Quintana even referred to “the trend of replacing ‘pedagogy’ with ‘educational sciences’” (1984, p. 16), which in his view became commonplace in Spain from 1968 onwards.

The stances adopted by Spanish academics in the field of education oscillated in this regard between: (a) a distinction that led them to adhere unconditionally to one of them; (b) the integration of both; or (c) an indiscriminate use of the two terms.

In respect of the latter, Fermoso (2003), for example, stated that “among us [university professors], we speak indistinctly of ‘Pedagogy’, ‘Educational Sciences’ and ‘Theory of Education’” (p. 62). That being said, Sáez Carreras (2007) pointed out that, for practical purposes, it is due to administrative decisions that a certain term ends up being adopted or abandoned. Böhm (2015) stated that “the divergence between pedagogy(ies) and educational science(s) is aggravated by the fact that political and financial patronage clearly favours educational sciences” (p. 20). This was especially true in undergraduate university studies in this country, where the term “social education” was preferred over that of “social pedagogy” (Úcar, 1996).

We have pointed out that German pedagogy arrived in Spain at the beginning of the 20th century, while the French and English traditions did so in the middle of the century4. This explains why the entry of the latter was experienced in the pedagogical profession as a loss of the initial unity that had been provided by pedagogy. Ortega pointed out that, in the 1970s, “the disaggregation of ‘Pedagogy’ into ‘Educational Sciences’ took place following ‘scientific’ adhesions” (2005, p. 112).

I have characterized this fact, which Ortega refers to as the scientific misunderstanding, elsewhere (Úcar, 2013). It is a misunderstanding that stems from the historical trajectory followed by pedagogy in Spain in its quest to become a social science on a par with the rest of the so-called social sciences. As Meirieu pointed out:

in order to acquire their pedigree within the university, the “educational sciences” had to prove their “scientificity”. And, for fear that they would not be considered “true sciences”, they redoubled their commitment to pointillism and positivism: this is how the experimental method was imposed, preferably loaded with quantitative data, to the detriment of the critical reading of works, careful observation of practices and decoding of the issues at stake (2016, p.111).

This may be one of the problems that has contributed most to the lack of academic and social prestige awarded to (social) pedagogy and is also at the base of a large part of the evils that Trilla (2018) referred to in the aforementioned book.

In my view, this misunderstanding equally reveals a desire and a complex that can be associated with pedagogy. The desire to have a status equivalent to that of the rest of the social sciences, and a certain complex deriving from the fact of not being socially and academically recognized. Both of these factors are linked to the history of pedagogy and the evolution of the social sciences in our country.

Brezinka (2002) analysed the evolution of pedagogy from its beginnings as a “theory of the art of educating” linked to educational practice, up until its total departure from practice to become a scientific pedagogy. And he also pointed out that the value of that theory, not yet scientific, lay in the security it provided educators with when acting in educational practice.

This evolution of pedagogy towards the scientific field is explainable by the status held by both practices and arts in the 19th century. As De la Orden pointed out:

When I was studying pedagogy at the University of Madrid in the 1950s, I became convinced that we had to leave behind essay writing and philosophy if we wanted to become a scientific community. It would probably take a lot of effort for our discipline to come to resemble a physical-natural science, but that was the model (2007, p. 3.).

Being seen as a practice or an art did not help pedagogy when it came to being considered a science, since neither was taken into account by an academia at that time determined to focus on theory and the scientific method. If pedagogy was to achieve “scientific” status among the different social sciences, it would need to distance itself from being considered as a practical or artistic activity and become a science whose main objective was to produce theory. It seemed that only by becoming scientific could pedagogy achieve the necessary status to be one more science among the different social sciences.

Brezinka revealed how the search to satisfy this desire brought with it a high price: that of abandoning practice. The resulting pedagogy was more academic, less practical, and more scholarly; a pedagogy, in short, that “increases insecurity and confusion, and creates resignation among educators” (2002, p. 401).

The same German author explained that the pedagogy initiated in the 18th century generated high expectations in relation to what could be achieved by a pedagogy turned science. Time has come to show that these expectations were not met, however: there were no improvements in educational practice and it did not become possible to better or more reliably predict the results of educational actions.

Deprived of a base on which to anchor and build its discourse, scientific pedagogy – and university pedagogues themselves – have, in general in this country, had a diffuse identity and academic production little connected with educational actions and practices. Brezinka concluded by pointing out that pejorative views of pedagogy can probably be attributed to the disenchantment generated by not having met expectations in relation to the predictive capacity and security that it was supposed to provide for educators and educational processes. This is what De la Orden (2004) highlighted in relation to so-called experimental pedagogy: “its journey has not been totally satisfactory, because it has not been able to fully articulate its desire for scientificity and its commitment to optimization” (cited in López Gonzalez, 2012, p.48).

Brezinka’s analysis may help explain why there was a subsequent rupture in the Franco-British current in terms of its spheres of influence. The scientific perspective stemming from the English-speaking tradition and part of the Francophone tradition, which advocates rethinking the field of education from science, mainly influences how pedagogy studies are carried out at universities. “Since then,” Garcés states, referring to the scientific perspective in education, “the field of theoretical and practical reflection on education has done nothing but fragment and diversify exponentially” (2020, p. 32).

In relation to the quandary over pedagogy/educational sciences and the clash between the aforementioned two traditions and the German one, in the 1980s the question was asked of whether Social Pedagogy should be replaced by the Sociology of Education5 on the university pedagogy curriculum. The passage of time has finally led to the two coexisting on current university curricula, where we find degrees in both Pedagogy and Social education.

We have already pointed out that the perspective of educational sciences derives from the Francophone current, following, among others, the ideas of Durkheim (Sáez Carreras, 2007). But said current also brought with it a whole series of practical experiences in sociocultural and educational work aiming to respond to the problems that, in the framework of the prevailing dictatorship in our country at the time, were occurring in the peripheral neighbourhoods of numerous cities totally neglected by the centralism of the regime. I have noted elsewhere that:

The first educational actions to be carried out in community settings, in the 1960s and 1970s, were conceived within a context of need and as a result of at least two processes: one being community reconstruction, and the other the protest or struggle against the dictatorship. Seeking to meet one of these objectives or another, informal social agents, in most cases lacking theoretical training and technical tools, voluntarily engaged in socio-community work with large doses of enthusiasm and confidence in the future. They were the forerunners of today’s social educators. Those first socio-educational intervenors, aware of their training deficiencies, eagerly drank from any source that would help them organize, systematize and, ultimately, improve their own practices (Úcar, 2002, p. 5).

One of these sources was the socio-educational work being carried out in France at the time. Young Spaniards, who had experienced different cultural and educational practices in their neighbouring country, began to reproduce them in Spain, and socio-cultural and specialized education initiatives from the French-speaking world were soon spreading throughout this country.

All of the above resulted in two parallel trajectories here in Spain, that of social pedagogy, which was taught at universities (in competition with the sociology of education, imported as part of the scientific perspective) and that of social education which, under a very varied set of names, was put into practice in many neighbourhoods. Two trajectories that separated the academics (theoreticians) from the professionals (practitioners). Interestingly, this separation between academics and professionals in pedagogy/social education has also occurred in other European countries6. It should be noted, however, that there has been a clear commitment to convergence and the development of a joint discourse between academics and professionals in recent years (Ortega, Caride, and Úcar, 2013).

The result of these different trajectories is the still discussed relationship between (social) pedagogy and social education. A discussion that occurs in both the theoretical and professional spheres.

Questions regarding the relationship between social education and pedagogy or, more specifically, about whether social educators are pedagogues or vice versa, arise often in the first years of university degree training. Suffice it to say for the moment that the academic legislation establishes two different degrees that train two, in theory at least, different professionals. Although both are part of the education sector, the professional profile of social educators and the jobs that they can access today are more identifiable and concrete than those that can be accessed by professionals in pedagogy.

However, the aforementioned professional differences do not prevent the two from working within the integrative and vehicular framework of pedagogy. In other words, although social educators are clearly not pedagogues from a professional point of view, their professional activity is clearly pedagogical.

3. LIFE STRUCTURED INTO PEDAGOGIES

Social pedagogy is a pedagogy that is taught neither by the family nor by the school. This was the idea posited by Bäumer in 1920s Germany, following the ideas of Nohl (Quintana, 1999; Pérez Serrano, 2003). The latter author was one of the first scholars of what could be called practical social pedagogy, and what we now call social education in the Spanish context. Life was thus structured into pedagogies. There was a family pedagogy that took place within the family, a school pedagogy that took place in the school, and a social pedagogy that, unlike the other two, was not situated within any specific institution. These authors pointed out that it was up to society and the State to implement it. Bäumer stated that this pedagogy existed “in special, public or private, institutions […] that provided socio-educational assistance” (Quintana, 1999, pp. 91-92).

Practical social pedagogy, developed above all by Nohl from the beginning of the 20th century onwards, is a pedagogy that seeks to remedy the problems and needs created by industrial society. A pedagogy that could be considered a pedagogy of need and that the aforementioned author characterized as the “third space”; one that is related to neither family nor school. In fact, this is the perspective that reached Spanish universities. The social pedagogy that began to be taught in Spanish universities from the second half of the 20th century onwards was a pedagogy focused mainly on maladjusted children and youth (Quintana, 1984).

It would not be inaccurate to identify a parallelism between the stages that classical sociology established for the processes of socialization and the very structuring of life through pedagogies. The primary socialization that occurs in the family corresponds to family pedagogy. Secondary socialization, which takes place at school, is acquired through school pedagogy. Finally, tertiary socialization, also called resocialization (Rössner, 1977, cited in Fermoso, 1990, p. 160), is the one that, situated within the perspective of the “third space” and the pedagogy of need, corresponds to social pedagogy.

We have explained elsewhere how the evolution of what is termed social in the second half of the 20th century brought an end to this classic interpretation of what we understand by the term social. Nowadays, socialization or, more accurately, socializations, given that it is not a unified or homogeneous process, are continuous; they are distributed widely; they occur in physical and digital environments; and they take place throughout our existence (Úcar, 2016).

We can state something similar in relation to the three pedagogies defined above. The distinction is useful in simple societies, where agents, socializers and educators are clearly identifiable and the institutions that host them are separate and clearly differentiated. In complex societies like ours, however, where institutions are increasingly permeable to the physical, digital and sociocultural environment, and whose educational and socializing agencies are diverse, diffuse and not always completely transparent, ruptures and differentiations tend to become blurred.

4. ADMINISTRATIVE RUPTURES IN EDUCATION IN THE NAME OF SCIENCE

I have already referred to how administrative decisions can end up generating situations or even specific cultures that stretch out over time and can be very difficult to reverse, even when they are identified as being ineffective or inefficient. I am referring here to the University Reform Law (LRU) of 1983, led by the socialist minister Jose Mª Maravall. This reform, which modernized the Spanish university system both structurally and functionally (Vega Gil, 1997), established the so-called areas of scientific knowledge employed at Spanish universities.

These areas were administrative delimitations used to categorize university professors. The areas of knowledge are “those fields of knowledge characterized by the homogeneity of their object of knowledge, a common historical tradition and the existence of national or international research communities” (Royal Decree 1888/1984, of September 26, which regulates calls for the allocation of places in university teaching bodies, page 31051). In the specific sector of education, the areas of knowledge pertaining to pedagogy were established as: Theory and history of education; Didactics and school organization; and Research and Diagnostic Methods in Education7.

Beyond its obvious arbitrariness, this rupture in the education sector may not have been of any great importance if it were not for the clause that prescribed how university careers and research pathways had to be followed within a specific area of knowledge. And that supervision of and decisions on these careers fell under the jurisdiction of the full professors responsible for each area.

For many years, this organizational system prevailed in shaping the teaching and research bodies of university departments and designing the curricula of what were then known as diplomatura and licenciatura courses, but are nowadays referred to as degrees. Even today, the individual areas of knowledge still configure the tribunals that judge candidates for a career in teaching and research. It is true that, since the mid-1990s, agencies and regulations have begun to come into play that mediate these decisions (the six-year research periods and the quality agencies of the State and the individual autonomous regions), but the teaching staff continues to be defined as “from Theory”, “from Didactics” or “from Methods”.

In my view, this organizational system has contributed decisively to impoverishing educational research in our country; to arbitrarily fragmenting research topics and questions; to promoting the creation of pressure groups within each area; to generating internal struggles in each area and between areas; and, finally, to hindering and even penalizing attempts to transcend the limits that these areas impose on research.

Throughout my professional career, I have seen how pressure groups from different areas of knowledge, embodied in university departments, have disputed knowledge, disciplines or methodologies appearing in the education sector. As an emerging sector in the 1980s and 1990s, the field of social education was an object of desire and dispute among the different areas of knowledge. Although for over 30 years there was talk of eliminating these areas of knowledge, today it is not even discussed, despite the fact that they continue to impose a good part of the limitations that I have mentioned. As Fernández-Armesto pointed out, “academic specialization is a terrible instrument of discord that divides us into ghettos, isolating us together with those who think like us” (2016, p. 280).

These ruptures in education have not facilitated the design and configuration of the university degree in social education in any way. If we add to this the fact that, also by dint of administrative decision, no regulation exists regarding the minimum core8 content of the degree at the national level, then it will come as no surprise that results in the training of graduates in social education vary greatly between the different autonomous regions. Negotiations and disputes between areas of knowledge in relation to which subjects will comprise each degree in each autonomous region are further complicated by the added possibility – since there is no prior regulation in this regard – of proposing names of subjects that situate them in one area or another due purely to the way in which they are formulated.

5. BY WAY OF CONCLUSION: ARTICULATING RUPTURES IN EDUCATION

Over the last few decades, attempts have been made to find different ways of managing the failure of these ruptures in education to adapt to realities within which they do not readily fit. Hybridization, interrelation, articulation, intermediation, intercommunication and permeabilization have increasingly shaped the path that has been followed to facilitate said adaptation and enable, at the same time, understanding of a social and educational complexity that was gradually becoming more visible. One might say that, although some of these ruptures are still in full operation, the passage of time is making them obsolete or scarcely operational9.

Lifelong learning replaces the “formal” criterion in the universe of educational actions. A substitution that is not merely one of terminology, but also one of substance, since it places not the one who teaches but the one who learns at the centre of the educational act. And what is more, as I have pointed out, it opens the door to educational research on everything that escapes formalization. So-called informal learning is an aspect that, from my point of view, social education must consider as a priority line of research. Social education, as a pedagogy of everyday life, aims to accompany people in their learning to help them help themselves, as Nohl, among others, sustained. Much of this learning is experiential and generated, often in a non-transparent way, in the interactions that people have in our daily lives. It is precisely the field in which social education has to investigate in order to build new knowledge that helps social education professionals improve and optimize their actions.

Something similar has happened to the concept of formal as happened with the pedagogies that structured life in watertight and isolated containers. It has been the very evolution of what is considered to be social and the interpenetration and articulation of the different stages of life in a continuum that has made the formal approach increasingly obsolete.

The debate between pedagogy and educational sciences has also faded over time. The emergence of complexity as a new category that permeates the entire field of knowledge; the questioning of what is truly “scientific” and, likewise, of the alleged “objectivity” of knowledge; the evolution of the social sciences themselves, with their contribution of new perspectives and research methods; and the increasing permeabilization between different ways of producing or creating knowledge… are all factors that, among others, have contributed to downplaying the question: What does it mean to do science or to be a science? And in the meantime, the need or demand to emphasize how “scientific” a given social science is has also been relegated to the background. By means of a global comparative study on social pedagogy, carried out from academic, (higher) education and professional training perspectives, Janer and Úcar (2020) have shown that pedagogy/social education is considered a science, a practice and an art.

Finally, it is worth noting that the administrative rupture of the university education sector remains in place10. That being said, the intermediation progressively being implemented by the different University Quality Agencies in the autonomous regions with respect to the selection of university teaching and research candidates is contributing to reducing the impact of these ruptures. As is the increasingly common networking between research faculty from different areas of knowledge connected by research topics or problems, breaking down the walls that the areas of knowledge have sought to establish.

We do not know if the future will bring new ruptures, but current trends point towards increasingly connected and linked scenarios in the education sector as a whole. This evolution would seem to point towards an educational galaxy with two completely permeable and interrelated nebulae: that of training, oriented towards content learning and the acquisition of skills for productive, artistic and professional life; and that of relational life and civic coexistence, aimed more at learning and experiencing values, emotions and citizen and community life. It would not be unreasonable to think that the former will be mostly technologically mediated, while the latter will develop, also mostly, but not only, as face-to-face interaction. It is plausible to think that what we now call social education will be mainly found in the latter sphere.

REFERENCES

Böhm, W. (2015). ¿Pedagogía y/o ciencia(s) de la educación? En J. Ortega Esteban, Última lection (pp. 17-36). Universidad de Salamanca.

Branches-Chyrek, R., & Süncker, H. (2009). Will Social pedagogy disappear in Germany? En J. Kornbeck & N. Rosendal Jensen (Eds.), The diversity of Social Pedagogy in Europe (pp. 169-189) Europäischer Hochschulverlag GmbH & Co. KG.

Brezinka, W. (2002). Sobre las esperanzas del educador y la imperfección de la pedagogía. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 223, 399-415. https://revistadepedagogia.org/wp-content/uploads/2007/06/223-01.pdf

Caride, J. A. (2004). ¿Qué añade lo “Social” al sustantivo “Pedagogía”? Pedagogía Social. Revista interuniversitaria, 11, Segunda época, Diciembre, 55-85. http://e-spacio.uned.es/fez/view.php?pid=bibliuned:revistaPS-2004-11-2040

Caride, J. A. (2020). La (in)soportable levedad de la educación no formal y las realidades cotidianas de la educación social. Laplage em Revista, 6(2), 37-58. https://doi.org/10.24115/S2446-6220202062908p.37-58

Castro, M.ª M., Ferrer, G., Majado, Mª. F., Rodríguez, J., Vera, J., Zafra, M., y Zapico, M.ª H. (2007). La escuela en la comunidad. La comunidad en la escuela. Graó.

Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Educadoras y Educadores Sociales (CGCEES). (2020). El Consejo General de Colegios de Educación Social plantea la incorporación de la Educación Social al Sistema Educativo presentando aportaciones al Proyecto de Ley Orgánica de Modificación de la LOE (LOMLOE). https://www.consejoeducacionsocial.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/NPAportacionesCGCEESaLOMLOE27mayo2020.pdf

De la Orden, A. (2007). El nuevo horizonte de la investigación pedagógica. Revista electrónica de investigación educativa, 9(1), 1-22. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1607-40412007000100010

Fermoso, P. (1990). Sociología de la educación. Alamex.

Fermoso, P. (1994). Pedagogía social: fundamentación científica. Herder.

Fermoso, P. (2003). ¿Pedagogía social o ciencia de la educación social? Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, Segunda época, 10, 61-84. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/1078220.pdf

Fernández-Armesto, F. (2016). Un pie en el río. Sobre el cambio y los límites de la evolución. Turner.

Galán Carretero, D. (2019). La realidad de los educadores sociales en el Estado español. Experiencia evolutiva en los centros de educación secundaria de Extremadura. Educació Social. Revista d’Intervenció Socioeducativa, 71, 79-104. https://www.raco.cat/index.php/EducacioSocial/article/download/350968/446457

Garcés, M. (2020). Escuela de aprendices. Galaxia Gutenber.

Janer Hidalgo, A., & Úcar, X. (2020). Social Pedagogy in the World Today: An Analysis of the Academic, Training and Professional Perspectives. The British Journal of Social Work, 50(3), 701-721. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcz025

Kornbeck, J. (2009). Important but widely misunderstood: the problem of defining social pedagogy in Europe. En J. Kornbeck & N. Rosendal Jensen (Eds.), The diversity of Social Pedagogy in Europe. Studies in Comparative Social Pedagogies and International Social Work and Social Policy (pp. 211-235) Europäischer Hochschulverlag GmbH & Co. KG.

Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de diciembre, por la que se modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación. (B. O. E. de 30 de diciembre de 2020, Núm. 340). https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2020/12/29/3/dof/spa/pdf

López González, E. (2012). Explicación científica y pedagogía: algunas notas. En M.ª Castro Morera (Ed.), Elogio a la pedagogía científica. Un “liber amicorum” para Arturo de la Orden Hoz (pp. 33-55). Grafididma.

March, M. X. & Orte, C. (Coords.). (2014). La pedagogía social y la escuela. Los retos socioeducativos de la institución escolar en el siglo XXI. Octaedro.

Meirieu, P. (2016). Recuperar la pedagogía. De lugares comunes a conceptos claves. Paidós.

Orden UNI/1191/2020, de 3 de diciembre, por la que se modifica el Anexo I del Real Decreto 1312/2007, de 5 de octubre, por el que se establece la acreditación nacional para el acceso de cuerpos docentes universitarios (B. O. E. de 15 de diciembre del 2020, Núm. 326). https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2020/12/15/pdfs/BOE-A-2020-16147.pdf

Ortega, J. (2005). Pedagogía social y pedagogía escolar: La educación social en la escuela. Revista de Educación, 336, 111-127. https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/dam/jcr:e59fbef2-e52e-4f14-b1bd-4c6736d40411/re33607-pdf.pdf

Ortega, J., Caride, J. A. & Úcar, X. (2013). La Pedagogía Social en la formación-profesionalización de los educadores y las educadoras sociales, o de cuando el pasado construye futuros. RES. Revista de Educación Social, 17, 2-24. http://www.eduso.net/res/?b=21&c=227&n=716

Ortega, J. & Caride, J. A. (2015). From Germany to Spain: Origins and transitions of Social Pedagogy through 20th Century Europe. En J. Kornbeck & X. Úcar (Eds.), Latin American Social Pedagogy: relaying concepts, values and methods between Europe and the Americas (pp. 7-24). EVH/Academicpress GmbH. https://www.academia.edu/35491221/De_Alemania_a_Espan_a_Ori_genes_y_tra_nsitos_de_la_Pedagogi_a_Social_por_la_Europa_del_siglo_XX_pdf

Pérez Serrano, G. (2003). Pedagogía social-educación social. Construcción científica e intervención práctica. Narcea.

Piaget, J. (1993). Jan Amos Comenio. Perspectivas, 23(1-2), 183-209. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02195034

Quintana, J. M.ª (1984). Pedagogía social. Dykinson.

Quintana, J. M.ª (1999). Textos clásicos de pedagogía social. Nau llibres.

Real Decreto 1888/1984, de 26 de septiembre, por el que se regulan los concursos para la provisión de plazas de los Cuerpos docentes universitarios. (B. O. E. de 26 de octubre de 1984, Núm. 257). https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/1984/10/26/pdfs/A31051-31086.pdf

Real Decreto 1420/1991, de 30 de agosto, por el que se establece el título universitario oficial de Diplomado en Educación Social y las directrices generales propias de los planes de estudios conducentes a la obtención de aquél.(B. O. E. de 10 de octubre de 1991, Núm. 243). https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/1991/10/10/pdfs/A32891-32892.pdf

Rosa, H. (2012). Aliénation et accélération. Vers une théorie critique de la modernité tardive. La Découverte.

Rosendal, N. (2009). Will social pedagogy become an academic discipline in Denmark? En J. Kornbeck & N. Rosendal Jensen (Eds.), The diversity of Social Pedagogy in Europe. Studies in Comparative Social Pedagogies and International Social Work and Social Policy (pp. 169-189). Europäischer Hochschulverlag GmbH & Co. KG.

Sáez Carreras, J. & García Molina, J. (2006). Pedagogía social. Pensar la educación social como profesión. Alianza.

Sáez Carreras, J. (Coord.). (2007). Pedagogía social. Pearson Prentice Hall.

Sloterdijk, P. (2013). Has de cambiar tu vida. 2ª Impresión. Pre-Textos.

Sloterdijk, P. (2016). Experimentos con uno mismo. Una conversación con Carlos Oliveira. Pre-Textos.

Trilla Bernet, J. (2018). La moda reaccionaria en educación. Laertes.

Úcar, X. (1996). Los estudios de educación social y la animación sociocultural. Claves de Educación Social, 2, 18-27. https://www.eduso.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/2_articulos_2.pdf

Úcar, X. (2002). Medio siglo de animación sociocultural en España: Balance y perspectivas. Revista Iberoamericana de educación, 28, 1-22. https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/artpub/2002/125615/revibeedu_a2002n28p1.pdf

Úcar, X. (2011). Social pedagogy: beyond disciplinary traditions and cultural contexts? En J. Kornbeck & N. Rosendal Jensen (Eds.), Social Pedagogy for the entire human lifespan. Vol I, (125-156) Europäischer Hochschulverlag GmbH & Co. KG. https://www.academia.edu/591453/Social_pedagogy_beyond_disciplinary_traditions_and_cultural_contexts_2011_

Úcar, X. (2013). Exploring different perspectives of Social Pedagogy: towards a complex and integrated approach. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 21(36), 1-15. http://epaa.asu.edu/ojsarticle/view/1282

Úcar, X. (2016). Pedagogías de lo social. UOC. https://www.editorialuoc.com/pedagogias-de-lo-social

Úcar, X. (2021). Social pedagogy, social education and social work in Spain: Convergent paths. International Journal of Social Pedagogy, 10(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.444.ijsp.2021.v10.x.001

Vega Gil, L. (1997). La reforma educativa en España (1970-1990). Educar. Curitiba, 13, 101-128. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.175

_______________________________

1. See: Sloterdijk, 2013, pp. 446-458 and Piaget, 1993.

2. The General Council of Educator and Social Educator Colleges of Spain (CGCEES) (2020) ends a document dated May 27, 2020 as follows: “we request the incorporation of Social Educators within the education system as a tool for promoting education and compensating for inequalities in education through their inclusion in the LOMLOE (Organic Act Modifying the Organic Act on Education, approved in December 2020), and as a right of citizens demanding Social Education, an education for the 21st Century”. See: https://www.consejoeducacionsocial.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/NPAportacionesCGCEESaLOMLOE27mayo2020.pdf

3. These are certainly not the only influences underlying what is now Social Education in Spain. But they are, without a doubt, the most important. Among other influences we can cite, at least, critical pedagogy and popular and adult education, which came from Latin America at the hands of Paulo Freire, and the community development processes that took place in Spain in the 1960s, above all, within the social work framework. See Úcar, 2021.

4. To expand on these three traditions and the way in which they influenced the shaping of social pedagogy and social education in Spain, see: Ortega, 2005; Sáez Carreras and García Molina, 2006; Sáez Carreras, 2007; Úcar, 2011; Ortega, Caride and Úcar, 2013; Ortega and Caride, 2015.

5. See Quintana, 1984; Fermoso, 2003; Caride, 2004; Sáez Carreras and Molina, 2006. Quintana justified these differences by stating that “the Sociology of education is a descriptive science, while social pedagogy is a normative science” (1984, p. 26). Fermoso (2003), for his part, explained the struggles taking place between the Sociology and Pedagogy departments to obtain or maintain ownership of these disciplines at Spanish universities.

6. See, in this regard, Braches-Chyrek & Sünker, 2009; Rosendal, 2009; Kornbeck, 2009. It is very likely that the misunderstanding of scientificity to which I referred previously is one of the reasons that also explains these problems and tensions in Europe.

7. Although I refer only to these three areas of knowledge in this text, there are others that also make up this sector. They are generically referred to as Special didactics: Didactics of Corporal Expression; Didactics of Musical Expression; Didactics of Musical, Plastic and Corporal Expression (Disaggregated); Didactics of Plastic Expression; Didactics of Language and Literature; Didactics of Mathematics; Didactics of the Experimental Sciences; and Didactics of the Social Sciences

8. By this I mean the basic subjects or content that must be shared, at a national level, by all people who obtain a degree in social education, regardless of where they do so in Spain.

9. Such a statement may be too bold if we are to heed the educational policies of our country which, as always, lag very far behind sociocultural changes and arrive very late. Article 5 bis of the recent Organic Act for the Improvement of Educational Quality (LOMCE) states the following: “Non-formal education within the framework of a culture of lifelong learning will include all those activities, means and areas of education that take place outside formal education and that are aimed at people of any age with a special interest in childhood and youth, that have educational value in themselves and have been expressly organized to meet educational objectives in various areas of life such as self-improvement, promoting community values, socio-cultural animation, social participation, improving living conditions in relation to art, technology, recreation and sports, among others. The articulation and complementary nature of formal and non-formal education will be promoted so that the latter contributes to the acquisition of skills for the full development of the personality.” (p. 122882)

10. Annex I of the B. O. E. of December 15, 2020 contemplates accreditation committees for university teaching bodies, indicating the areas of knowledge assigned to each of them. In Education, it reaffirms the areas already indicated (Order UNI/1191/2020, of December 3, which modifies Annex I of Royal Decree 1312/2007, of October 5, establishing national accreditation for the access of university teaching bodies, page 114802).